When Doctors First Had to Ask Permission

The 1970s healthcare cost crisis sparked a revolution that changed medicine forever: utilization review, where bureaucrats began questioning doctors' decisions in real time.

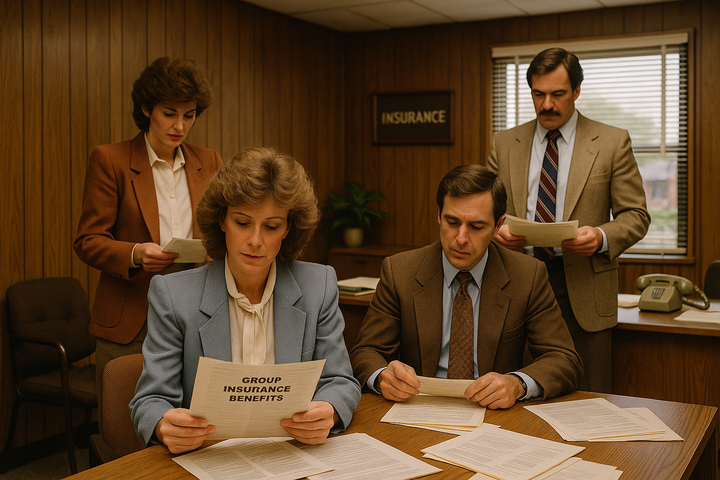

Picture this: It's 1975, and Dr. Sarah Mitchell is about to admit a patient for what she considers a necessary three-day hospital stay. But first, she has to pick up the phone and justify her decision to someone she's never met—a nurse reviewer working for the insurance company, armed with a checklist and the authority to say no. This awkward dance between medicine and money was brand new, and it was about to reshape American healthcare forever.

The birth of utilization review in the 1970s wasn't some grand master plan hatched in corporate boardrooms. It was a desperate response to a crisis that caught everyone off guard. Healthcare costs were exploding at a rate that made even seasoned insurance executives break into cold sweats. Between 1970 and 1979, national health expenditures nearly tripled, jumping from $75 billion to $215 billion. The traditional model of 'doctor orders, insurance pays' was hemorrhaging money faster than anyone could count it.

The Wild West of Medical Spending

Before utilization review, American healthcare operated like an all-you-can-eat buffet with someone else picking up the tab. Doctors made medical decisions in splendid isolation, hospitals filled beds because empty beds didn't generate revenue, and insurance companies wrote checks with remarkable faith in medical judgment. The fee-for-service system created perverse incentives: more tests meant more income, longer hospital stays meant higher profits, and questioning medical necessity was considered somewhere between rude and heretical.

Dr. Paul Ellwood, the Minneapolis physician who would later coin the term 'health maintenance organization,' watched this unfold with growing alarm. In 1970, he observed that American medicine had created a system where 'the economic incentives reward the physician for doing more rather than doing better.' It was an uncomfortable truth that most preferred to ignore—until the bills started arriving.

Enter the Reviewers

The first utilization review programs were crude affairs, often staffed by nurses armed with basic medical criteria and a healthy dose of skepticism. They reviewed hospital admissions, questioned lengthy stays, and—most controversially—sometimes overruled physician judgment. The process was clunky, adversarial, and deeply resented by doctors who saw it as an assault on their professional autonomy.

What made this particularly fascinating was how quickly the concept evolved. Early utilization review was reactive—reviewing care after it was delivered, like a medical audit. But by the mid-1970s, some plans were experimenting with concurrent review, actually monitoring patients during their hospital stays. The most ambitious programs attempted prospective review, requiring pre-authorization before expensive procedures or admissions.

The critical cost control mechanism that emerged wasn't just about saying no—it was about asking why. For the first time in American healthcare history, someone was systematically questioning whether each test, each procedure, each extra day in the hospital was truly necessary. The reviewers compared service requests against emerging clinical guidelines, looking for patterns of overutilization and waste.

The Backlash and the Breakthrough

Doctors hated it. The American Medical Association denounced utilization review as 'cookbook medicine' that reduced complex medical decisions to bureaucratic checklists. Hospital administrators complained about delays and administrative burden. Patients worried that some faceless reviewer would deny them needed care to save a few dollars.

But something interesting happened amid all the controversy: healthcare costs began to moderate, at least slightly, in organizations that implemented aggressive utilization review. More importantly, the data revealed uncomfortable truths about medical practice variation. The same condition might result in vastly different treatment approaches—and costs—depending on which doctor you saw, which hospital you entered, or which part of the country you lived in.

By 1979, utilization review had evolved from a desperate cost-cutting measure into something resembling a systematic approach to medical management. The crude checklists gave way to more sophisticated clinical criteria. The adversarial phone calls evolved into collaborative discussions between reviewers and physicians. Most significantly, the concept of medical necessity—previously assumed to be whatever a doctor ordered—now had to be justified and documented.

The Seeds of Modern Healthcare

Those awkward phone calls Dr. Mitchell made in 1975 planted seeds that would grow into the entire managed care industry. The utilization review techniques pioneered in the 1970s became the foundation for HMOs, PPOs, and virtually every cost control mechanism we see today. The basic questions first asked in that decade—Is this care necessary? Is there a less expensive alternative? How do we balance cost and quality?—still drive healthcare policy discussions nearly fifty years later.

What's remarkable is how prescient those early pioneers were. Modern UR systems increasingly leverage artificial intelligence and predictive analytics to make the same fundamental assessments those first nurse reviewers made with clipboards and determination. The technology has become vastly more sophisticated, but the core mission remains unchanged: ensuring patients receive appropriate care while controlling unnecessary spending.

The 1970s transformation from unlimited medical autonomy to systematic utilization review represents one of the most significant shifts in American healthcare history. It established the principle that medical decisions could—and should—be subject to external review, that healthcare resources weren't unlimited, and that someone needed to ask the hard questions about value and necessity. Whether you see this as necessary cost control or unwelcome interference probably depends on which side of that phone call you're on.